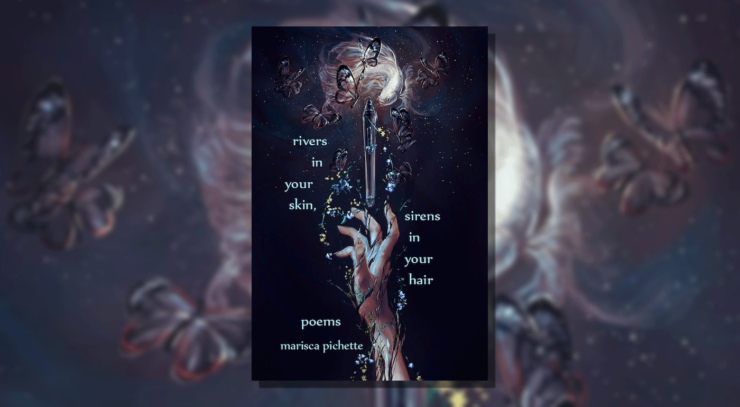

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover the first five poems in Marisca Pichette’s Rivers in Your Skin, Sirens in Your Hair, first published in 2023. Spoilers ahead, to the degree poetry makes spoilers meaningful.

“I braided my hair with eggshells & apple seeds, trussed together under a paisley pashmina.”

This week we cover Marisca Pichette’s “In Parting,” These Days Were Made For Us,” “The Size of Your Fist,” “Like Breathing,” and “Her Ribs Are Apple Wood.” We won’t attempt to summarize them—go instead and read them yourself.

What’s Cyclopean: Water is terrible and vital, and being afraid of it is an impossible paradox: “…tell me that you fear the ocean just like an eye fears a tear and the clouds fear the rain.”

Weirdbuilding: How do we decide what’s not normal? “…the kindness of strangers—the strangeness of kindness—the kind of strange only stranger than kind.”

Buy the Book

Rivers in Your Skin, Sirens in Your Hair

Anne’s Commentary

It was possible to summarize Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market,” as I did in our previous Poetry Month post—for all that was lost in trimming the rich detail from its narrative, there was a narrative, deceptively straightforward in the way of most fairy tales.

Summarizing the first five poems in Marisca Pichette’s rivers in your skin, sirens in your hair would be a whole ‘nother mission, one I’m not willing to accept, but its “impossibility” isn’t due to a lack of narrative. As Pichette writes in her introduction to the collection, she is a prose writer who “in poetry…never claimed to know what I was doing.” Yet, like “all creative work,” the poems “come from a desire to tell a new story, or an old story in a new way.” Compared to prose narrative, poetry offers “freedom from constraint, a space for authenticity.” Not surprisingly, then, her poems are written in free verse, a style that in avoiding set metrical schemes and rhyming patterns aims to imitate the authentic rhythms of speech. Much free verse, I find, more closely imitates the natural patterns and vagaries of thought, which in turn reflect those of a core metaphor of art, the river.

Appropriately, river is the first word in Pichette’s title.

What do rivers—and thoughts—do? They flow swift or sluggish or at just the right speed for safe and efficient navigation. They are deep or shallow, expansive or narrow, clear or murky, straight or meandering, treacherous with rapids or serene, nurturing or toxic. They can stick to one channel or braid out into many. They can flood, to beneficial or disastrous effect. They can collect all sorts of refuse or treasure, whatever falls into them or is dredged up from their beds, to be recombined and deposited downstream. They can run free or be locked into canals or constrained behind dams. They can plunge underground. They can peter out into stagnant marshes. They can make it to the sea, another core metaphor, representing consummation or communion, death or unbounded life.

Try to verbally summarize a river in a way that makes your audience experience it in full, as itself, the thing irreducible. Try to do the same thing with a poem of any depth. Easy enough: Type out the poem word for word, line break for line break. The poem, too, is irreducible, but as a printed work, it’s reproducible. Within the limitations of column space and copyright law, we can’t reproduce Pichette’s work here. As I’ve noted above, I decline to reduce it. The attempt would do nothing to further understanding of our discussion for someone who hasn’t read the poems.

My working theory is that the more prose-like the poem, the more summary can capture of it. Corollary: the more poetic the prose, the less summary can capture. The two literary modes lie on an infinitely subdivided continuum of verbal density.

Somewhere along their academic roads, students of literature may encounter Archibald MacLeish’s “Ars Poetica” and its closing dictum that “A poem should not mean/But be.” Nevertheless, teachers of literature remain human, whatever some grade-, and high-, and grad-school sufferers may believe, and humans like things to mean as well as to exist. Who among us, then, has not slid under the paltry shelter of a classroom desk when the teacher asked, “So, what’s this poem about?” Confronted with Kilmer or Wordsworth, the earnest (or satirical) student might have replied, “It’s about trees (or daffodils.)” Pressed, they might have added, “And how they’re beautiful!” or even “And how their beauty and perseverance and other anthropomorphized qualities can teach us important moral lessons!” The most advanced responders might go on about the pathetic fallacy, and how pathetic it is.

As for what Pichette’s “In parting” is about, what can I hazard from deep under my desk? Well, it’s about someone leaving home carrying a lot of weird stuff in a lot of weird places instead of more practical stuff in more practical suitcases or backpacks. Maybe this person is deranged, because what sane person braids “eggshells & apple seeds” into their hair and then ruins an expensive “paisley pashmina” by binding it over that sticky junk? Or maybe they’re a witch with magical uses for owl pellets, wax seals, “A doll, felted from my first cat’s fur. The jawbone of an English sheep.” They could even be outright monstrous, if we interpret the “pockets I’d accumulated” to mean actual pockets of skin, flesh and fat into which they’ve packed their miscellany of needful things; these pockets filled, they’ve even lined their throat “with academic papers & diary entries rolled up in rubber bands” and topped off the load with “bookshelves, carefully folded into the creases of my skin.”

Alternatively, we could fall back on the assumption that the baggage in the poem is metaphorical, though we might then feel obliged to figure out what each item stands for. I’d rather assume the weirdness is weirdness. Pichette encourages me to follow this inclination by stating that her collection is one of “speculative poetry,” which “tells a story outside of reality, after all.”

On the other hand, she adds: “By leaving reality behind, we access the rawest truths about ourselves.” Doesn’t that imply that weird poetry, and by extension all weird art, is necessarily metaphorical? That granted, are readers obliged to dig for correspondences between the fabulous and the mundane?

In truth, unless they have to turn in papers on said correspondences, readers can do whatever they want. Closing her introduction, Pichette encourages us to respond freely: “I offer these poems to you. I hope you see in them a glimmer of memory, an echo of home.”

So here are my glimmers and echoes, what the five first poems mean to me:

“In parting:” I imagine myself sitting on the bus next to that grotesquely overstuffed human duffel bag and sharing some of their clementines while listening to their story about why they had to leave home. Clementines are extra juicy when the refrigerator chill has been driven off by body heat. Chocolate, on the other hand, fares poorly in flesh-pockets. I will be supplying the bonbons on this trip.

“These days were made for us:” Here’s a debate that my duffel-bag companion-by-chance has on the bus with the old man sitting across the aisle from us. Night and rain are falling. The old man objects to my companion’s remark that the rain is made for them in particular—he’s just been waiting for a chance to correct our grievous misconceptions about the world. He doesn’t realize my companion may be a witch—or maybe he does, and that’s the problem. We two withstand his fearful arguments. We know that teardrops can be turned to diamonds, and that seagulls love the ocean as an eye loves tears and the clouds love rain. Things bigger than us may be awe-stirring rather than terrifying. Mud lives to mark our passing, and would the old crank like a clementine and some truffles?

“the size of your fist:” After the old man drifts into a snoring doze, I randomly remark that a human heart is indeed fist-sized. This draws from my companion the story of how they labored to replace their heart after it was stolen. Golem clay, though it could hold their incised cri of love me back, proved brittle. Metals all had contraindications: Too cold, too heavy, too weak, too prone to verdigris. A heart of glass cannot be dropped. An oak, storm-felled but with heartwood still sap-dripping life, did the trick for my companion—at least their heartwood-heart has learned to beat.

“like breathing:” That’s what the woman sitting alone in front of us asks: “Like breathing?” She has knelt up against the back of her seat to look down at us. In the lightning flashes the storm has begun to toss, her pupils glow silver. She’s a vampire, my companion whispers to me, but the woman proves to be kind enough in her strangeness and refrains from feasting on any of us mortal passengers, even though I offer her the snoring old man. Only, how well she bears the weight of her centuries makes me think of all the years I’ve toiled through, for what? When I get off the bus, the deluge intensifies. I have to swim home, and fish have taken over my living room. Have they finally drunk enough, I ask them, but fish never will respond to sarcasm.

“Her ribs are apple wood:” My bus companion has followed me home. We float above the still-offended fish, and the maybe-witch tells me the story of an enchantment. There was an apple tree who was dead and slowly rotting and so cold she radiated cold, colding. When bees nevertheless accepted her invitation to hive in her hole-gored heart, she lived again with them. I wonder if my companion was rival-transformed into that apple tree. This, I think, would make sense in light of the story they told earlier about making themself a new heart, and how it was another tree’s heartwood that worked best. What happened to the bees, though? Did they get to keep the apple tree’s hole-gored heart?

And—that’s what the poems mean. I’ve been binge-reading the rest of rivers in your skin, sirens in your hair. The poems are as toothsome as well-buttered popcorn, but more nourishing.

Thanks to Marisca Pichette for the dreams already inspired, and the dreams yet to come!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Humans birth litters of holidays. Ancient Rome offered two or three per week, their equivalent of our predictable semi-secular weekend. The Catholic Church deals days among saints like cards. And modern governments, non-profits, and random groups of mischief-makers declare observances at will. On our eclipse road trip, we nitpicked Jack’s holiday conquest strategy from The Nightmare Before Christmas. I suggested that one really ought to start with smaller and less well-defended holidays, whereupon the inhabitants of the back seat checked online and planted their flag on International Beaver Day.

All of which is to say, some holidays are tied to seasons and events, while others are more-or-less random in their timing. One could make an argument for placing National Poetry Month in the dead of winter when we hunger for color, or in the fall as an inducement to put short and sweet readings at the start of the school year. But April feels appropriate to me. It’s a liminal month of snow and sunlight. It’s a better time than the January new year for resolutions and novelty. Poems have some kinship with garden seedlings and seed packets, dense compressions of idea. This year April also hosts Passover—my family’s haggadah is about half poetry, and though I find new additions every year, wails arise if I cut any.

I’m drawn to poems about transformation. Poetry can be so intensely visceral in its sensory and emotional detail, cutting to the heart of how we fear and desire change. Field Guide to Invasive Species of Minnesota sticks with me two years later for the way it links personal, species, and planetary transmutation: all body horror and adaptation and transcendence. Pichette’s poems strike me similarly, though they focus more on the individual narrator. Metaphors and memories are folded into the body—maybe deliberately, maybe out of necessity. The circumstances of heart-crafting and home-leaving are left to inference. What matters is the bookshelves stored in your wrinkles, the pine needles and glass beads between your collarbones.

“In Parting” puts me in mind of sculptures that stuff skeletons with flowers and sparkling jewelry, an aesthetic so common I can’t now find the actual one I’m thinking of. What’s the home being left? Is this a memento mori for parting from life, or the past that comes with us in every transition? Is it the fantasy of grabbing everything that matters in a refugee evacuation? Maybe it’s hoarding, being able to leave a place only by becoming everything it embodied. But I imagine the gloriously chaotic literal: wrists dangling with clattering bangles, hair bound tight with dyed eggshells, throat clogged with everything you’ve dared put to paper.

“The Size of Your Fist” focuses on a single organ, a dark Three Little Pigs of the heart. Like “In Parting,” it makes me think about sculpture, trying different materials until one comes out right—or getting meaning out of the whole series rather than just the final product. It’s telling that it starts with “golem clay”—ove me back the sacred replacement for truth, but golems turn against their creators always. And does the material matter more than the method of creation? Metal is made in the same mold as clay, before moving on to the oven for blown glass and then whittling wood shard by shard. An oak heart makes me think of Sarah Pinsker’s brilliant “Where Oaken Hearts Do Gather,” though of course the phrase as a byword for strength is much older. Pichette’s oak heart doesn’t feel impregnable, only just strong enough to function—maybe hearts need to be oak-strong in order to work at all between bruises.

“Like Breathing” blurs the lines between body and water—bodies being mostly water after all, and terribly vulnerable to being either less or more water than ideal. Thunder and lightning are the organs and energy that make them go, pulse and digestion. This poem also brings us “backstroking” back to a home, maybe the one that got left behind in “In Parting.” The living room is full of fish, “washed clean.” Homes, too, are vulnerable to too much water—at least human homes. Perhaps more transformation is in order, to be able to live like fish in that flood, having “finally drunk enough.”

Next week, we begin our new longread with the first six chapters of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary.

God, this was wonderful. If we’d read stuff like this instead of Shakespeare at school I would be an entirely different person.

I started peeking at the summary, but had to just go ahead and order the paperback and will catch up when it arrives.

Now I just have to decide if I’m really ready to jump into Pet Sematary, or if I’ll have to skip this long read!